Update: Critical satellite data abruptly terminated

The erosion of our weather safety framework continues

Note: there has been some updated information today regarding the loss of the DMSP data I wrote about in yesterday’s newsletter. Given this info and the importance of this story, I have pulled the content from yesterday’s newsletter and updated it with the new information to make it a standalone post.

NOAA announced through a data change notice yesterday that all access to data from the Defense Meteorological Satellite Program (DMSP) was being terminated. The US Space Force has a webpage that provides an overview of the DMSP, which is a polar orbiting satellite system in which satellites with a variety of meteorological instrumentation provide crucial information from data sparse regions. The DMSP has been in operations for more than 50 years, and initially the data gathered was classified. In 1972, the data was declassified and began to be used by the civilian meteorological community.

A colleague shared with me today that Fleet Numerical Meteorology and Oceanography Center, the Naval meteorology group responsible for decoding and disseminating the DMSP data, put out a public release earlier in the week that stated that the data was being discontinued because the DMSP ground data processing system is running an end-of-life operating system and cannot be upgraded due to cybersecurity concerns. For the Department of Defense, the DMSP was in the process of being phased out by the end of 2026 as a new satellite system has replaced it (more on that below), so from the DoD’s perspective this appears to be just an acceleration of an already planned action.

The loss of this data has significant impacts on the operational meteorological community, and the most urgent and alarming is the impact on hurricane forecasting. Data from the DMSP’s Special Sensor Microwave Imager Sounder (SSMIS) is a crucial tool for forecasting tropical cyclones because it allows forecasters to be able to see beneath the clouds and look at the internal structure of a tropical cyclone, akin to an MRI or X-ray of a human for a doctor.

This animated GIF posted (click on the image if needed to see the animation) on BlueSky by my colleague Dr. Kim Wood is a compelling example of how SSMIS data can be used by hurricane forecasters. In this case, the standard infrared imagery only showed that Otis was getting better organized. The SSMIS microwave data goes “under the hood” of the storm to clearly show that a well developed eyewall has formed beneath the cirrus cloud canopy. This enabled NHC forecasters to precisely locate the eye - likely improving the track forecast - and much better anticipate the rapid intensification that would take Hurricane Otis to a catastrophic category 5 before landfall near Acapulco.

SSMIS data is particularly crucial for forecasting tropical cyclones that are in data sparse regions like the Pacific and tropical Atlantic, but even in areas with radar and reconnaissance data they are an important tool. I encourage you to read this article from tropical meteorologist Michael Lowry and this BlueSky post from James Franklin, the retired chief of the Hurricane Specialist Unit at the National Hurricane Center, that provide key insights on the impacts of losing the SSMIS data from tropical meteorology experts. James in particular provides some important context on the potential real-world impacts of the loss of the SSMIS data from someone who has sat in the NHC forecast chair hundreds of times.

As I alluded to above, for DoD SSMIS data is being replaced by the Weather System Follow-on-Microwave (WSF-M) satellite, which started providing operational data to the DoD in late April. However, this data is not being provided to the civilian community at this time, and I have been unable to find any plans for the data to be shared with the civilian weather community. NOAA provided comments today about the data loss on the civilian side to Bloomberg reporters Lauren Rosenthal and Brian Sullivan for a story they published:

In a statement Friday, NOAA communications director Kim Doster said the military satellite data is just one piece of a “robust suite of hurricane forecasting and modeling tools.” Doster said storm models still include data from other satellite systems and from NOAA's hurricane hunter aircraft, among other sources.

“NOAA’s data sources are fully capable of providing a complete suite of cutting-edge data and models that ensure the gold-standard weather forecasting the American people deserve,” Doster said.

First off, I continue to be disappointed in the fact the NOAA Communications seems to be devolving into providing meaningless buzzwords like “cutting-edge data” and “gold-standard weather forecasting” to try to distract from obvious ways in which NOAA’s operational capacity is being degraded. Because this is once again - similar to the NOAA statement in April about NWS staff reductions - a farcical statement that is easily refuted.

Of course there will still be hurricane forecasting tools available, but this hurricane forecasting tool (SSMIS) will not be. Polar orbiting satellites by their nature only provide data at any given point on the globe periodically, so it is a uniquely precious (I can’t think of a better phrase) data source. While there will still be some microwave data available from other polar orbiting satellites, the loss of SSMIS will result in a 50% reduction in the data available for the applications discussed above. Furthermore, the microwave data that will remain is significantly poorer in resolution and will not provide forecasters with data of nearly the kind of quality and robustness that SSMIS provides.

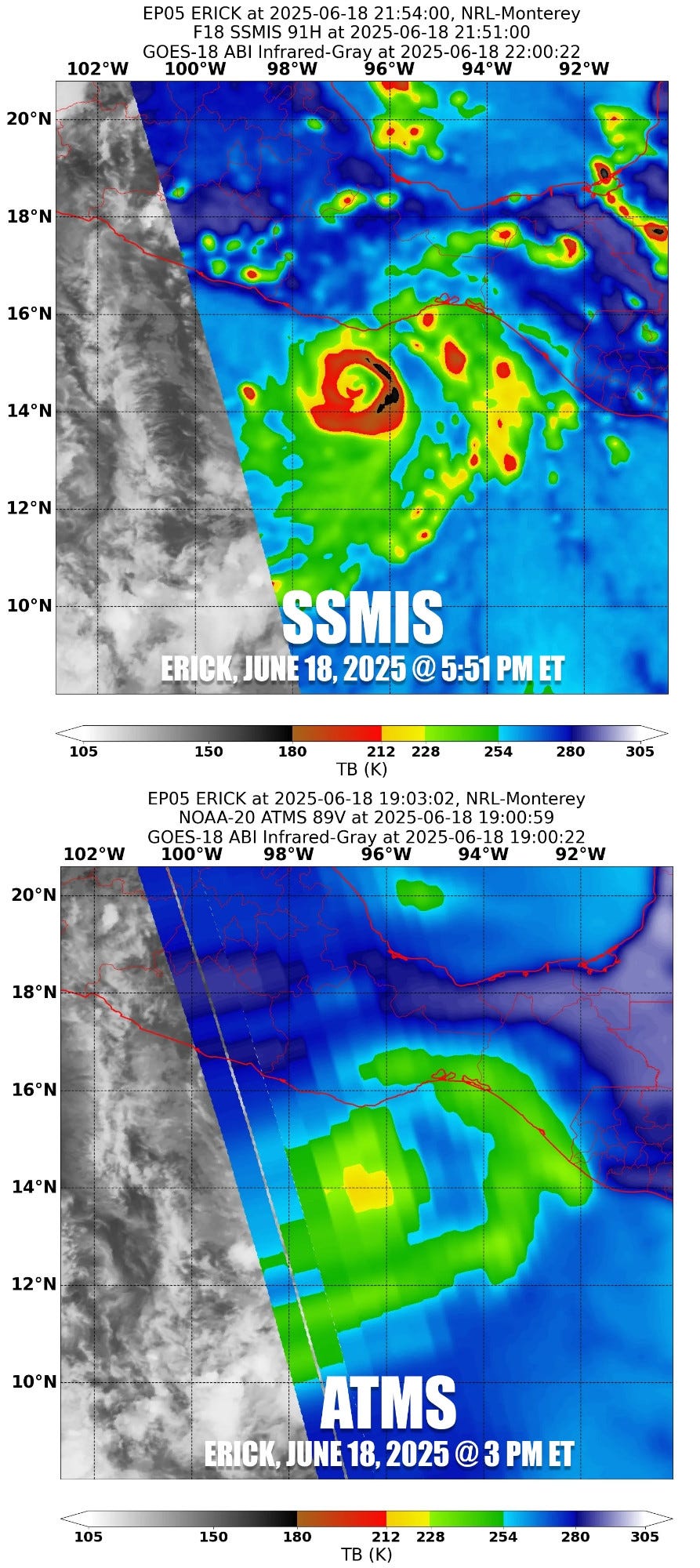

This image from Michael Lowry’s recent BlueSky post shows microwave images of Hurricane Erick from similar times earlier this month, the top image from the DMSP SSMIS instrument and the bottom image from the NOAA ATMS polar orbiting microwave instrument. The difference in image resolution and quality is obvious I think even to a lay person: the eyewall of Erick is very easy to discern in the SSMIS product, while the ATMS image shows little detail that would be useful to a meteorologist for hurricane forecasting.

I should stress that tropical forecasting is by no means the only way in which DMSP SSMIS data is used by the meteorological community. This data is important for marine forecasting, ice monitoring and analysis, and a variety of other meteorological applications.

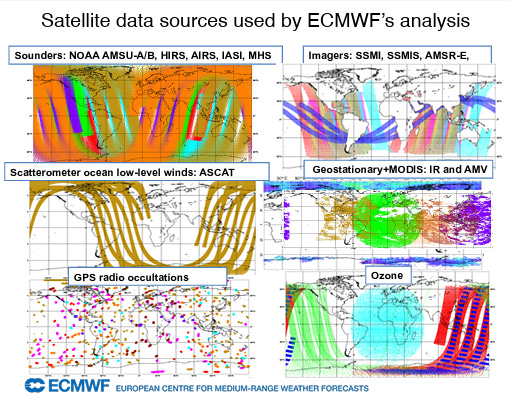

One of those applications is data assimilation for the numerical weather prediction modeling systems. Both the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts and NOAA’s Environmental Modeling Center use SSMIS data in the data assimilation for the operational computer models that the community uses for all of its forecasting applications. When discussion focused on the loss of upper air balloon soundings at a number of NWS locations a couple of months ago, one of the things we discussed was that computer models had become less reliant upon that data because of improved use of satellite data in the models.

I did some research today to try to get a better sense of the relative utility of the various datasets that go into the numerical weather prediction models, looking at papers and websites from a variety of national meteorological modeling centers. The bottom line from what I could discern is that even with all of the additional remote sensing data that now goes into the models, the upper air balloon radiosonde data is still one of the most important datasets for model quality. Meanwhile the SSMIS data is (luckily) one of the lesser impact datasets for the models.

Of course, though, losing the SSMIS data is yet another data source lost to the models at a time that upper air balloon flights have also been reduced due to NWS staffing issues. Really, this example of relative data quality to the models is illustrative of where the weather community finds itself right now. The quality of the warnings and forecasts that serve to keep the public safe is not reliant upon any one particular type of data, it is the end product from a huge interconnected framework of humans (scientists, communicators, technicians, etc.), organizations, data collection systems, analysis and forecast computing systems, etc. A given individual part of that framework will have more relative importance than another, even to the point that the same data source may have different relative importance to different parts of the framework (e.g., SSMIS data is more important to the hurricane forecast than to the computer models).

However, regardless of the relative importance of each part of the framework, when you start taking pieces away, even the ones of lesser importance, the framework is by definition less than it was when you started. Over the last few months, we have lost more and more pieces of the framework, from all of the expertise lost with the staff reductions to the loss of Climate.Gov to the reduced upper air flights - and on and on up to and including this loss of the SSMIS data. Regardless of what NOAA spokespeople may try to tell us, with each day and each loss I become more convinced that we are less safe and less prepared for what the atmosphere will be increasingly sending our way in the coming weeks, months and years.

Will the loss of this data affect in any way mid latitude forecasting?