BalancedWx Special: Tragic flash flooding in the Texas Hill Country

Sometimes the worst case scenario sadly happens

As we enter the day after the horrific flash flooding that occurred along the Guadalupe River in the Texas Hill Country early on July 4th, the full magnitude of the tragedy is gradually and painfully becoming clearer. CNN is reporting late this morning that 27 people are confirmed dead, and that at least 20 girls are missing from a youth camp. Kerrville City Manager Dalton Rice told CNN that 27 girls were missing from Camp Mystic, and that officials are unable to say how many more people could be missing in the floods. “We do not have an accurate count, and we don’t even want to begin to estimate at this time,” he said.

An overarching point that I think needs to be emphasized about this event is just what an absolute worst case scenario it was. A common refrain in the emergency management and disaster community is that a disaster is rarely the result of one failure or event, it typically is the end result of a cascade of multiple things that go wrong. For this tragedy, the obvious overarching contributing factors are that the flash flood event occurred in the middle of the night when people are typically asleep and less likely to be able to take protective action, and that it occurred at the start of a long summer holiday weekend when campgrounds and resorts such as the ones that cluster along the Guadalupe River are most likely to be full.

Looking at the meteorology, let’s start with a radar loop from the Laughlin AFB radar running from about 1 am to 5 am. On the left side of this loop is radar reflectivity, and on the right side is radar estimated total rainfall. One thing that you can immediately see is how isolated the rainfall event was in the area west and northwest of San Antonio. While heavier rainfall was more widespread overnight in the area farther north between San Angelo and Killeen, for this part of Texas, the heaviest rain was localized over this particular region near and west of Kerrville.

The area west of Kerrville is the headwaters for the Guadalupe River. There is a north fork and a south fork of the river that meet near the community of Hunt, seen on the map west of Kerrville. The south fork runs along Texas Highway 39 which is the highway you can see heading southwest out of Hunt, while the north fork runs along Honey Creek Ranch Road (FM1340), which is the road running west out of Hunt. Campgrounds line both forks of the river as you can see for yourself if you look at this area on Google Maps.

Looking at the Multi-radar Multi-sensor (MRMS) 3 hourly rainfall ending at 4 am CT Friday, you can see that the absolute heaviest rain of 6-10” in 3 hours fell almost perfectly aligned with the south fork of the Guadalupe southwest of Hunt, which is the gold square on the map. This means that all of the runoff from this swath of heavy rain was maximized to feed directly into the river.

As I talked about in this flash flood science deep dive a couple of months ago, rainfall rates play a huge part in how much runoff occurs along with the underlying surface. This MRMS product, FLASH unit streamflow, gives meteorologists an estimate of the amount of runoff and inundation that is occurring by running MRMS rainfall estimates through a hydrologic model that can be run very quickly, making the data useful for flash flood warning decisions. In this case, the model was showing widespread values greater than 20 across the basin of the south fork of the Guadalupe, values indicative of potentially catastrophic flash flooding. The extreme rainfall rates combined with the vulnerable terrain of the region resulted in massive runoff.

Also, if you look at the loop of rainfall above, you can see that the storms were moving southwest to northeast, meaning they were moving along the flow of the river. Research has shown that storms moving down a river channel produce larger hydrologic response than if a storm is moving up the river channel. The movement of the storms here was likely another factor in maximizing the magnitude of the floodwave.

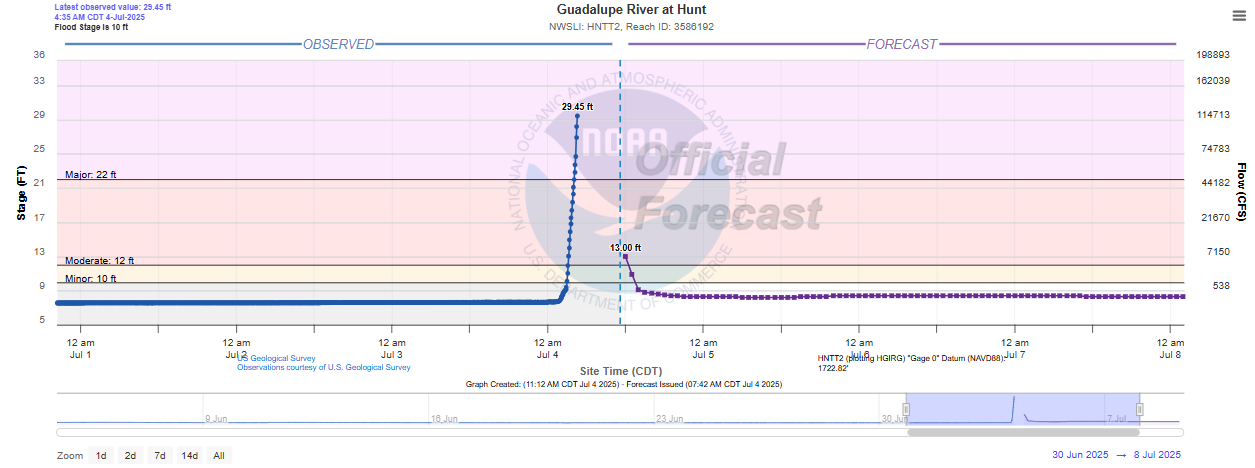

The USGS river gage at Hunt showed the devastating result of all of this, as the river rose from a stage of 7.7’ and a flow of 8 cubic feet per second at 1:10 am as the rain began, to a a stage of 29.45’ and a flow of 120,000 cubic feet per second at 4:35 am. The gage failed at this point. The rain gage at the site measured 6.49” of rain in the 3 hours up to the point of gage failure, and as we can see in the MRMS 3 hour estimate above, even heavier rain likely fell southwest of Hunt. It is almost impossible to imagine or convey the reality of what those gage measurements mean. Essentially, at 1:10 am the river was a tranquil almost dry riverbed, and by 4:30 am it was a raging flood with more water flowing than the average flow over Niagara Falls.

Again, this was all happening in the worst case environment of the middle of the night in a remote area with numerous campgrounds. The question then naturally turns to what sort of information did people in the area have to potentially be prepared for an event such as this. To start, the NWS office in Austin/San Antonio - the office with responsibility for this area - issued a flood watch at 1:18 pm CT on Thursday, so about 12 hours before the rainfall really started in earnest. It was a pretty “standard” flood watch that included Kerr County - the county where this event happened - and called for widespread rainfall of 1 to 3 inches with isolated amounts of 5 to 7 inches.

The NWS Weather Prediction Center is responsible for issuing “mesoscale precipitation discussions” similar to the Storm Prediction Center’s mesoscale discussions, only for flash flooding. As this BlueSky thread from WPC forecaster Peter Mullinax highlights, WPC issued a number of these discussions leading up to and during the event. In particular, this one issued at 6:10 pm CDT really did a good job of outlining the potential of what could happen during the overnight hours, and did so several hours ahead of time. These discussions are meant to give people within the weather and warning community, including broadcast meteorologists, additional insight and situational awareness about flash flood situations. I have no idea obviously who may have read this particular product, but it should have helped anyone who did be aware of the potential presented by this meteorological situation.

As far as warnings are concerned, the NWS issued the initial flash flood warning for Kerr County at 1:14 am CT. This was really early on in the rainfall event as you can see from the radar loop above, and the warning specifically highlighted Hunt and included a “considerable” impact-based warning (IBW) tag for life-threatening flash flooding. Many initial flash flood warnings do not include this tag, which is often added in subsequent issuances as potential flash flood impacts start to become clearer to NWS forecasters. The fact that it was included from the start, and that the warning was issued so early are, in my opinion, signs of a very proactive warning strategy by the office. The inclusion of the considerable tag means that Wireless Emergency Alerts (WEA) on cell phones would have been activated by this initial warning, obviously dependent upon cellular coverage in the area.

The warning was subsequently updated at 1:46 am CT and 3:19 am CT with additional information about radar rainfall estimates. At 3:35 am CT, the warning was extended until 7 am. At 4:03 am CT, the warning was upgraded to a flash flood emergency with a “catastrophic” IBW tag, and the emergency also specifically highlighted that the Guadalupe River at Hunt was flooding. The flash flood emergency would have produced another round of WEA activations.

In summary, while there are certainly ways I could see in hindsight where the forecasts and/or warnings could have been subtly improved, overall in my opinion given the data available, WPC and the WFO did a solid job of service and information provision given what we can see in the public datafeed. In particular, the initial flash flood warning coming as early as it did and with a “considerable” tag was a proactive step to use the best tool the NWS has to alert the public in the region that a life-threatening event was unfolding.

This was not a situation with an obvious tropical cyclone to focus on or where the models were depicting widespread catastrophic heavy rainfall. It was a situation that the weather community faces a number of times a year: relatively subtle atmospheric disturbances capable of focusing and intensifying heavy rain producing storms in a region. In this case, the moisture was particularly high because of the remnants of tropical storm Barry and the anomalously warm Gulf. Regardless, it was an overall regime of subtle weather features where the heaviest rain is governed by very small scale processes in the atmosphere which as I have discussed many times are very difficult for the models or humans to anticipate.

Hopefully I have explained here that in this case, similar to the tragic Wheeling, WV flash flood a couple of weeks ago, this was truly a low probability, worst case scenario where the absolute maximum in rainfall happened to coincide with the headwaters of a particularly flash flood prone river with a lot of human beings along it. In this case it also happened in the middle of the night on the 4th of July, exacerbating the human toll. The reality is that the state of the science does not allow us to know that a small location like the south fork of the Guadalupe River is going to get 8” of rain in a 3 hour period even a couple of hours ahead of time, let alone with the kind of lead time that would, for example, keep people from camping in that area on a given night. The best that we can do is to develop better models with better probabilistic information that can be communicated in a way that helps people make better, more proactive decisions. This is the goal of the Forecasting a Continuum of Environmental Threats (FACETs) project that I worked on with NOAA. Additionally, NSSL has worked on development of tools such as Warn-on-Forecast high resolution atmospheric models coupled with hydrologic models like FLASH, showing promise to be able to provide the NWS and its partners with guidance that could help provide more specific information for threats such as these. Of course, I feel compelled to point out that all of this research would be eliminated given the President’s budget proposal to eliminate NOAA’s Office of Oceanic Research.

It is increasingly clear that what transpired this Fourth of July along the Guadalupe River is going to be an infamous weather event that will unfortunately be remembered for a long time. I am heartbroken as I work through all of this data and information, knowing the human toll that has resulted, and my heart goes out to all who have been devastated by this event. I do not want to participate in a blame game here, and there will be plenty of time in the coming weeks and months to evaluate what happened and try to learn to improve how we keep people safer from these events going forward. Having said all that, given the comments about this event that are being reported in the media and the increasing debates happening on social media, I felt it was important to try to produce at least an initial summary of this event, and I encourage you to read other thoughtful pieces by colleagues Marshall Shepherd and Matt Lanza.

I will conclude by saying this: just as what I have been able to see about this event shows me the NWS did a solid job, similarly there is little evidence that any of the recent cuts to NOAA/NWS negatively impacted services for this event, regardless of what may be being said on social media. It is possible that the reduction in balloon releases could have had some impact on model forecasts, but that would require more detailed examination. Additionally, I of course have no knowledge of what staffing was like at the NWS office, and if typical decision support to emergency managers was able to be provided.

Having said all that, this is clearly yet another event that shows the importance of having a robust, properly resourced NWS that is able to provide accurate warnings and forecasts at any time of the day or night, as well as the importance of NOAA Research if we want to improve our capacity to forecast and warn for these events. It also shows the importance of other federal agencies for community preparedness and response to these events. For example, the river gage at Hunt that documented the incredible rise of the Guadalupe River is operated by the United States Geologic Survey (USGS). There is already concern in our community about the state of the USGS stream gage network, and the USGS is slated for significant budget cuts in the President’s budget (along with most other scientific agencies) which could leave this crucial network even more vulnerable. Bottom line, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that we are on the wrong path as a society if we are trying to have fewer of these sorts of tragedies in our future.